A Recurrent Neural-Network-Based Real-Time Dynamic Model for Soft Continuum Manipulators

Published:

In March 2021, Tariverdi et al. published ‘A Recurrent Neural-Network-Based Real-Time Dynamic Model for Soft Continuum Manipulators’ in ‘Frontiers in Robotics and AI’ focusing on dynamic modeling problem of soft continuum manipulators. Their method is based on using recurrent neural network architecture to predict the motion of manipulators in real-time.

In this blog post, I intend to explain the outcomes of their work by going over the reported results and to clearly identify the importance of the proposed approach for modeling the motion of soft continuum manipulators.

What are soft continuum manipulators? How can their dynamic behavior be modeled?

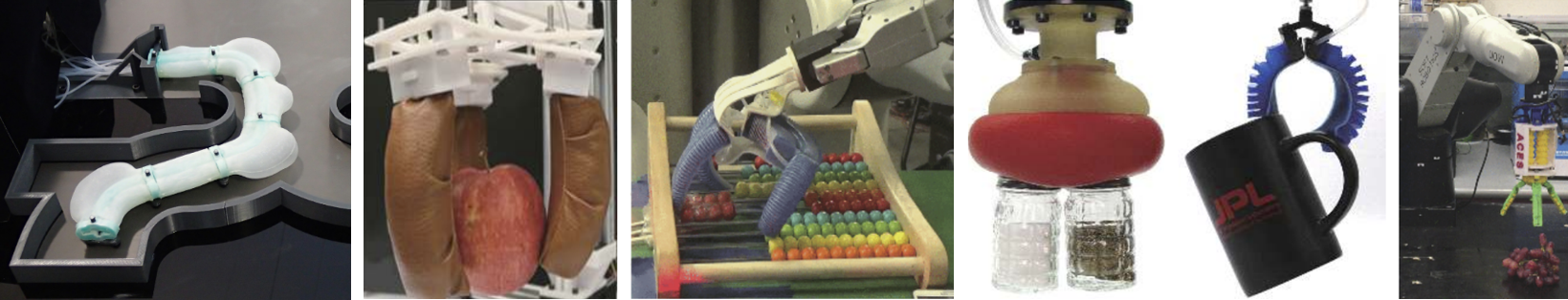

Soft continuum manipulators are composed of soft and elastic materials, enabling high flexibility and deformability in contrast to their counterparts, rigid robots. Their deformable structure allows them to physically comply with their environment and safely use them in complex workplaces with humans [1], [2]. Thanks to their adaptive structure and safe operability, soft continuum manipulators have been used in many applications, such as dexterous grasping [3], assistive devices [4], and minimally invasive surgeries like catheter-based endovascular intervention [5].

Figure-1 Example applications of soft continuum manipulators [6], [7]

Figure-1 Example applications of soft continuum manipulators [6], [7]

Despite their promising potential, soft continuum manipulators suffer from high degrees of freedom as it increases their modeling complexity. Even though there are different approaches in the literature, they all have some drawbacks. The first kind of these approaches relies on static or quasi-static assumptions preventing them from being used for cases with large deformations and high actuation frequencies. The second common approach can fully model the dynamics of the manipulator at the cost of high computational power, which inhibits their use in real-time modeling. Moreover, since they rely on finite elements and finite differences algorithms, they return discrete and limited-differentiable solutions, which is crucial for model-based controllers.

Alternative to these two approaches, neural network (NN) methods can represent complex partial differential equations (PDE) used to model the soft manipulators’ nonlinear behavior with high accuracy and unlimited differentiability. Moreover, by using a lower number of parameters compared to finite element methods, their computational power requirement is reduced. With the use of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which introduce the history into the input layer, the modeling accuracy for the dynamic systems can be further improved.

RNN-based Dynamic Model of Soft Continuum Manipulators

Authors propose an RNN-based approach to model the dynamics of soft continuum manipulator, which is scalable, can run in parallel and most importantly can predict the manipulator’s shape under applied forces and torques in real-time.

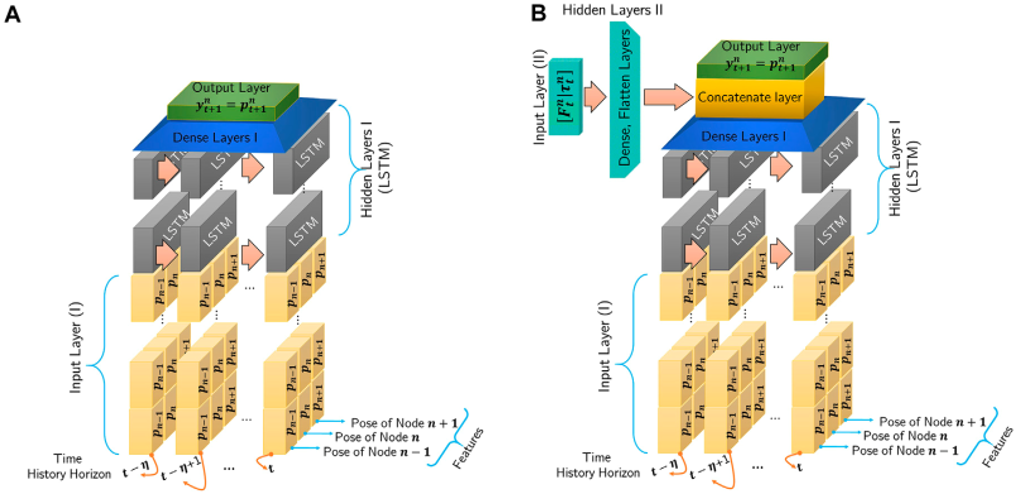

In the scope of this study, Tariverdi et al. implemented two different architectures of RNN to predict the position of a point on a soft continuum manipulator. The first network considers only the internal dynamics of the body while omitting the external forces. Stacks of long short-term memory (LSTM) layers are utilized for each time point, followed by a dense layer combining their outputs to include the position data history in prediction. The second network, on the other hand, includes the external stimuli by using dense layers and concatenating their outputs with the outputs of internal dynamics.

Figure-2 RNN architectures for pose prediction on soft continuum manipulator (A) without (B) with external forces

Figure-2 RNN architectures for pose prediction on soft continuum manipulator (A) without (B) with external forces

Performance Evaluation of The Proposed Model

Tariverdi et al. tested the proposed approach with simulated and physical systems to show its applicability and to evaluate its performance. While doing this, they checked for the following test scenarios,

- Simulated ellipse without external forces,

- Simulated cylindrical rod under external forces,

- Simulated cylindrical rod with and without external forces,

- Physical rod with two permanent magnets actuated by magnetic forces and torques.

During these tests, performance of the model is evaluated in terms of evaluation speed and prediction error.

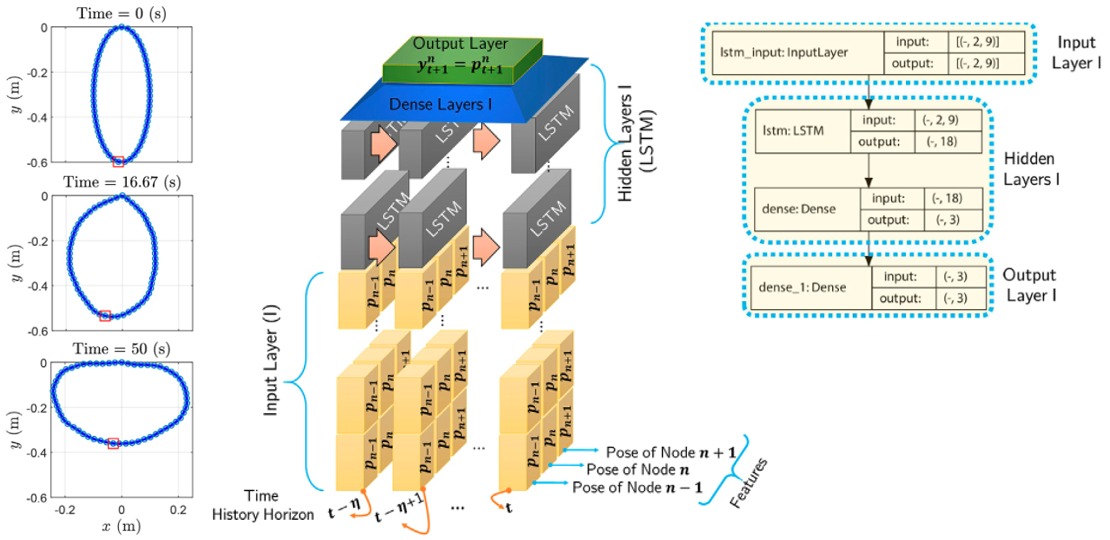

Simulation Results Without External Forces

In the first test case, a cylindrical rod is bent into a circle and fixed from two ends. After stretching to an elliptical shape and releasing, it starts moving without any external forces due to potential energies stored in the material. During this motion, a point on the rod is selected, and its position prediction by the proposed model is compared to the simulated data. After generating 50001 position samples from the analytical model and training the RNN-based model with 60% of this data, it is shown that the proposed model can predict the selected node’s position with 0.11%, 0.17%, and 0.02% maximum errors relative to the length of the manipulator in the x, y, and z-axes, respectively.

Figure-3 Simulated motion of circular soft beam without external force, used neural network architecture and layer sizes

Figure-3 Simulated motion of circular soft beam without external force, used neural network architecture and layer sizes

Following that, the trained model is tested again for different boundary conditions by changing the orientation of the fixed points. As the model is trained for a different boundary condition, the maximum relative error increased to 1.97%, 1.62%, and 0.37% in x, y, and z-axes, respectively, for this new test case.

| Mean Error (mm) | Max Error (mm) | Relative to Body Length (%) | |||||||

| x | y | z | x | y | z | x | y | z | |

| Trained Scenario | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 1.57 | 2.27 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| New Test Scenario | 3.37 | 3.70 | 4.22 | 26.33 | 21.71 | 4.92 | 1.97 | 1.62 | 0.37 |

Simulation Results With External Forces

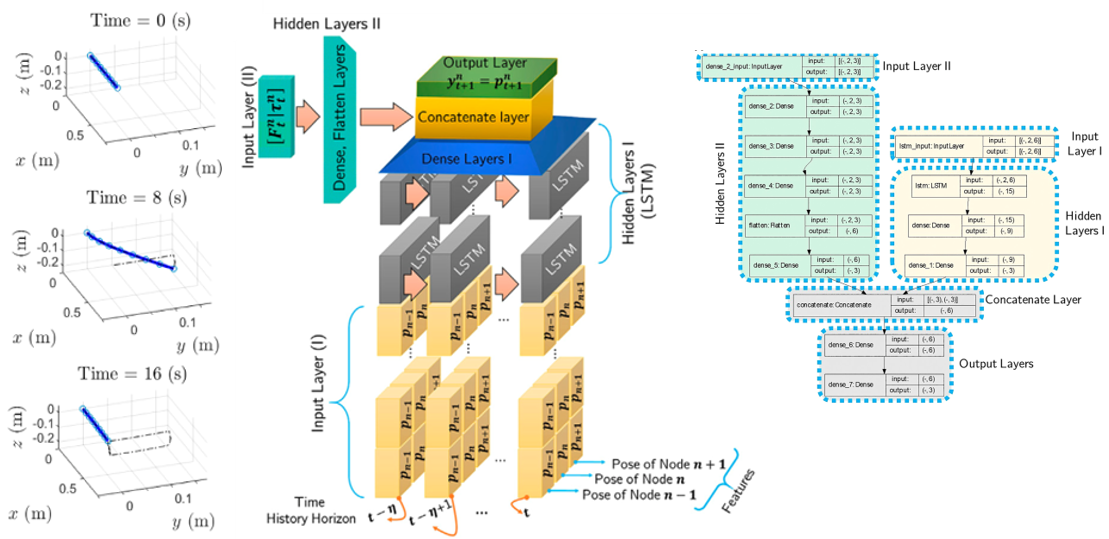

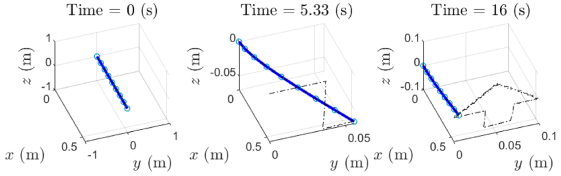

In the second test case, the cylindrical rod is forced from its tip point to follow a rectangular path, shown with dashed lines below. After generating 160001 position and force data from the analytical model, the RNN-based model shown below is trained with 60% of this data. Results show that the tip point position can be predicted with a maximum relative error of 0.71%, 0.36%, and 0.54% in the x, y, and z-axes, respectively.

Figure-4 Simulated motion of soft beam actuated by external forces, used neural network architecture and layer sizes

Figure-4 Simulated motion of soft beam actuated by external forces, used neural network architecture and layer sizes

Next, the trained model is tested to predict the tip point position as the external force moves it on an arrow-shaped path. Similar to the previous test case where there is no external force acting on the system, the maximum relative error increased to 1.90%, 1.00%, and 1.08% in the x, y, and z-axes, respectively.

Figure-5 Simulated motion of soft beam actuated by external forces

Figure-5 Simulated motion of soft beam actuated by external forces

| Mean Error (mm) | Max Error (mm) | Relative to Body Length (%) | |||||||

| x | y | z | x | y | z | x | y | z | |

| Trained Scenario | 1.70 | 0.69 | 1.41 | 3.58 | 1.80 | 2.73 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| New Test Scenario | 2.61 | 1.05 | 2.83 | 10.49 | 5.54 | 5.97 | 1.90 | 1.00 | 1.08 |

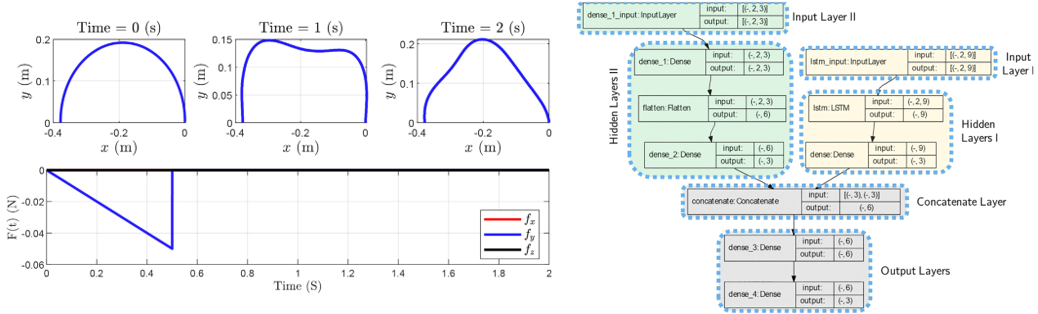

Simulation Results With and Without External Forces

The third and last simulation scenario includes both with and without external force cases during a single run. The cylindrical rod is initially bent into a semicircular shape for that purpose, and its endpoints are fixed. After applying a constantly increasing force to the midpoint of the rod for 0.5 seconds, the rod is released. Using the analytical model, 20001 position and force samples are generated throughout this run, and the RNN-based model is trained by 60% of this data. Similar to the previous test cases, the proposed model can predict the position of the selected node with a maximum relative error of 0.22%, 0.04%, and 0.37% in x, y, and z-axes, respectively.

Figure-6 Simulated motion of soft semi-circular beam actuated by changing external forces, and layer sizes of the used neural network architecture

Figure-6 Simulated motion of soft semi-circular beam actuated by changing external forces, and layer sizes of the used neural network architecture

At last, the trained model is retested for the case where a sinusoidal force is applied between t in [1,2] sec. As in previous cases, the model accuracy drops to 0.62%, 0.33%, and 1.35% in x, y, and z-axes, respectively.

| Mean Error (mm) | Max Error (mm) | Relative to Body Length (%) | |||||||

| x | y | z | x | y | z | x | y | z | |

| Trained Scenario | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.81 | 1.36 | 0.23 | 2.22 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.37 |

| New Test Scenario | 1.25 | 0.20 | 1.20 | 3.73 | 2.00 | 8.10 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 1.35 |

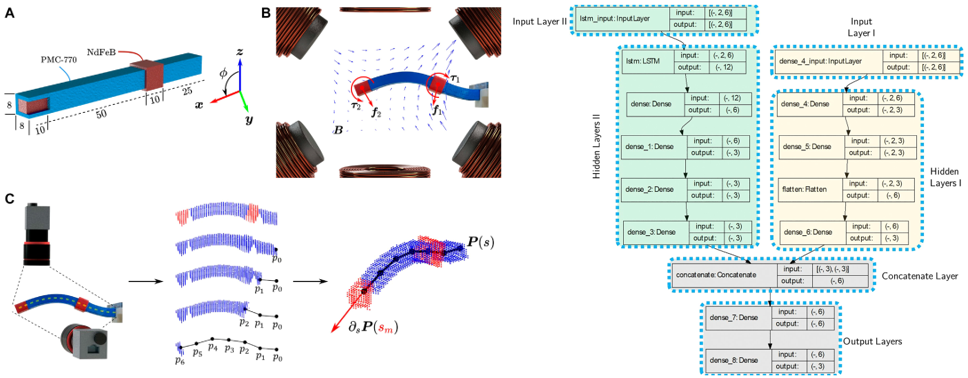

Physical Rod with two permanent magnets actuated by magnetic forces and torques

As the last test case, the proposed model’s performance is evaluated by running physical experiments instead of simulated motions of beams. For this purpose, a soft beam with two permanent magnets is designed and put into a workspace where the magnetic field can be controlled with an electromagnetic coil setup. The soft beam is moved and bent in 3D space during the experiments by manipulating the magnetic field, as its deflection is recorded with side and top-view cameras. By processing the recorded deflection data, nodes’ positions and applied magnetic force and torques are calculated. In the end, 669 position, force, and torque samples are collected by running physical experiments, and the neural network is trained by 60% of it. When the model-predicted orientation of distal and proximal nodes is compared with the Cosserat rod model prediction, it is shown that the proposed approach either outperforms or performs similarly to the commonly used Cosserat rod model.

Figure-7 Experimental setup, (A) soft beam with two permenant magnets, (B) electromagnetic coil system, and generated magnetic field, (C) visual feedback system and generated position data, (D) layer sizes if the used neural network architecture

Figure-7 Experimental setup, (A) soft beam with two permenant magnets, (B) electromagnetic coil system, and generated magnetic field, (C) visual feedback system and generated position data, (D) layer sizes if the used neural network architecture

| x-axis | y-axis | z-axis | |

| Maximum and mean error values for distal node | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| RNN-based model | 1.27°, 0.23° | 4.69°, 1.27° | 0.60°, 0.10° |

| Cosserat rod model | 3.56°, 0.82° | 10.55°, 5.03° | 4.02°, 2.22° |

| Maximum and mean error values for tip point | |||

| RNN-based model | 1.13°, 0.23° | 4.69°, 1.27° | 0.60°, 0.10° |

| Cosserat rod model | 1.55°, 0.36° | 7.22°, 3.51° | 3.29°, 1.99° |

Conclusion and Comments on The Results

In their paper, Tariverdi et al. proposed an RNN-based model to predict the dynamic motion of soft continuum manipulators. By running simulations and physical experiments, they showed that the proposed method achieves real-time pose and orientation prediction faster than analytical methods while achieving better or comparable prediction accuracy.

Although the model’s performance is tested and its applicability is proven in different scenarios, some points are still open to discussion.

- Even though the authors claimed that they proposed a single method for the dynamic model of soft continuum manipulators, they used different neural network architectures and approaches for all the test cases.

- The authors claimed that the model can predict the deformation of soft continuum manipulators in real time. However, they only evaluated its speed for a single node and did not test its performance to predict whole-body deformation.

- The authors did not show the model’s prediction performance for position and orientation of the measurement points.

- The authors claimed that the proposed method outperforms single, large networks proposed in the literature using a distributed architecture. However, they did not show any test results or comparisons.

To conclude, the proposed method and the tests presented in the paper show improved performance and provide a promising alternative method for the dynamic modeling soft continuum manipulators. However, clarifying the open points listed above could further improve its impact on the field.

References

[1] A. Tariverdi et al., “A Recurrent Neural-Network-Based Real-Time Dynamic Model for Soft Continuum Manipulators,” Front Robot AI, vol. 8, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.3389/frobt.2021.631303.

[2] S. Haddadin, A. de Luca, and A. Albu-Schäffer, “Robot collisions: A survey on detection, isolation, and identification,” IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 1292–1312, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1109/TRO.2017.2723903.

[3] R. K. Katzschmann, A. D. Marchese, and D. Rus, “Autonomous object manipulation using a soft planar grasping manipulator,” Soft Robot, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 155–164, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1089/soro.2015.0013.

[4] Y. Ansari, M. Manti, E. Falotico, Y. Mollard, M. Cianchetti, and C. Laschi, “Towards the development of a soft manipulator as an assistive robot for personal care of elderly people,” Int J Adv Robot Syst, vol. 14, no. 2, Mar. 2017, doi: 10.1177/1729881416687132.

[5] J. Burgner, P. J. Swaney, R. A. Lathrop, K. D. Weaver, and R. J. Webster, “Debulking from within: A robotic steerable cannula for intracerebral hemorrhage evacuation,” IEEE Trans Biomed Eng, vol. 60, no. 9, pp. 2567–2575, 2013, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2013.2260860.

[6] A. D. Marchese, R. K. Katzschmann, and D. Rus, “Whole arm planning for a soft and highly compliant 2D robotic manipulator,” in IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Oct. 2014, pp. 554–560. doi: 10.1109/IROS.2014.6942614.

[7] F. Xu and H. Wang, “Soft Robotics: Morphology and Morphology-inspired Motion Strategy,” IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 1500–1522, Sep. 2021, doi: 10.1109/JAS.2021.1004105.